In the next posts I want to briefly address certain issues with contemporary

Science – issues that I have been following with intense interest

and in which, sometimes, I also participated.

Let us start with Brian D. Josephson.

Brian

Josephson, 1973 Nobel Laureate in physics for discovering the effect

carrying his name and used in superconducting quantum interference

devices – used, for instance, in supersensitive magnetic field

detectors.

In 1988 my attention was drawn to Josephson’s paper

(written together with Michael Conrad and Dipankar Home) entitled

“Beyond quantum theory: a realist psycho-biological interpretation of physical reality” When discussing the current status of quantum theory, the authors

made the following comment:

"It should be noted that in the current interpretation we

do not assert that such processes as the state vector collapse

associated with quantum measurement are purely formal or imaginary

and have no corresponding physical correlates. Instead we assume the

mathematical filtering operation to correspond to a real physical

process the detailed nature of which may become clarified when the

biological aspects of the unified theory are taken fully into

account."

That remark

was one of the important starting points for my own research and

consequently led, in 1995, to “Event Enhanced Quantum Theory” (recently partly "rediscovered" by others under the term "hybrid classical-quantum dynamics").

Josephson, after receiving his Nobel Prize, naturally felt that he

had some freedom of choosing his research subjects and he used this

freedom to move in directions that were considered “pseudo-science”

by narrow-minded and non-curious “normal” career-seeking, or just

fearing-to-lose-their jobs, physicists. The topics in question

include things such as “water memory”, “the paranormal” and

“cold fusion” phenomena; all were being vehemently debunked and

the lives and careers of anyone daring to work on these topics were

being actively destroyed by the authoritarian defenders of “we know

it all” science.

In 1999

Josephson invited Jacques Benveniste to the Cavendish Laboratory in

Cambridge. Benveniste was, at that time, Directeur de Recherches at

INSERM, Digital Biology Laboratory, Clamart. In his talk at

Cambridge, Benveniste described in some detail experiments conducted

at INSERM with diluted biological agents and their peculiar

electromagnetic signatures. He stated that:

"These results strongly suggested the electromagnetic

nature of molecular signaling, heretofore unknown. This signal, that

is "memorized" and then carried by water, most likely

enables in vivo transmission of the molecular specific information."

At the end

of the talk (you can watch it here) Brian Josephson made a comment that the situation in Science is a

kind of a “power situation”, namely, that if the result is

sufficiently unusual, it is just ignored despite the evidence.

Benveniste noted that in the modern day, the situation is actually

much worse than it was in 1920, when you could publish unusual

results in a journal like Nature. Today Nature will give no space for

papers dealing with the electromagnetic carriers of the biological

information.

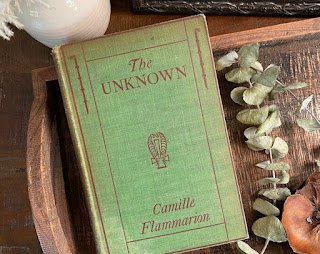

Brian

Josephson and Jacques Benveniste during the closing part of

Benveniste’ 1999 lecture in Cambridge

In 1997,

when I was organizing the Quantum Future conference, I invited

Josephson, and he agreed to come and give a talk on “The Paranormal

and the Platonic World”. At the last moment it transpired that he

could not come, since at the same time he was presenting his poster

at the First International Conference on Complex Systems near Boston.

Perhaps that was fortunate, since Springer

Verlag, the publisher of my Quantum Future conference would certainly

have vetoed the publishing of Josephson’s talk,

the same way it vetoed the paper by Vitiello.

Forbidden Subjects:

Censorship in Science

Certain

subjects are simply forbidden to talk about in some journals. What

does this sort of attitude, this kind of totalitarian control and

censorship, have to do with the ideals of Science? I think it is a

pure hypocrisy and politics. It may also have something to do with

certain psychological states. Josephson addresses the issue of

censorship in Science with this funny story:

"It is just an ordinary day at the headquarters of the

physics preprint archive. The operators are going through their daily

routine and are discussing what to do about recent emails:

Some "reader complaints" have come in

regarding preprints posted to the archive by Drs. Einstein and Yang.

Dr. Einstein, who is not even an academic, claims to have shown in

his preprint that mass and energy are equivalent, while Professor

Yang is suggesting, on the basis of an argument I find completely

unconvincing, that parity is not conserved in weak interactions. What

action shall I take?

Abject nonsense! Just call up their records and set

their 'barred' flags to TRUE.

And here's a letter from one 'Hans Bethe' supporting an

author whose paper we deleted from the archive as being

'inappropriate'.

Please don't bother me with all these day to day

matters! Prof. Bethe is not in the relevant 'field of expertise', so

by rule 23(ii) we simply ignore anything he says. Just delete his

email and send him rejection letter #5."

Then he goes

on with these personal comments:

"The first portion of the above exchange is fictional of

course, but might well have happened had Einstein and Yang had

dealings with the physics preprint archive arXiv.org, administered by

Cornell University, today. The second part is not fictional. The web

site archivefreedom.org has been set up to document experiences that

innovative physicists have had in dealing with the archive's

secretive operators, and here is my own story.

I have been fortunate in that, unlike the other

physicists involved, I may well be permitted to post preprints to the

archive at this time, though this proposition has not been put to the

test. I was however, very briefly, on the archive's blacklist myself

for doing things that displeased the operators, who permit contact

with them only anonymously via the alias 'moderation@arXiv.org'.

(I must immediately apologise for using the word

'blacklist': the organisation finds the term distasteful, saying

'that is your term -- we have no blacklist'. Let me therefore say

instead that, for a brief period, a flag was set in my archive record

to ensure that in the future when I logged on to deposit a preprint,

I would find myself barred from carrying out the required procedure.

Technically, they are right of course: a blacklist would be

represented on the server as a one-dimensional array listing the

members of the list, and setting a flag in one of the fields of an

array is not the same at all, if one is being pedantic. So I was not,

strictly speaking, on a blacklist, but the fact was, nevertheless,

that I could not upload my preprint to the server at that time).

What I did in response was to write to the

administration saying there seemed to be a 'system error', and would

they mind correcting it? Back came a message saying it had been

corrected and I could then upload my preprint. Was there really a

system error? I think not: Paul Ginsparg, the inventor of the

archive, does not make programming errors. I assume the archive

operators got together and decided that barring a Nobel Laureate from

depositing papers in the archive would create a bad impression, and

they decided it would be best to reinstate me."

I am

devoting so much space to this issue, because Josephson is not the

only one with a red “flag”. Red flags like those used by

arxiv.org are a disgrace to Science. In Science all should be in the

open, referees reports should be open to a public discussion and

criticism. No decisions should be taken behind closed doors. The fact

that openness is not the way things are done in these matters means

only one thing: private interests have taken over and Scientific

ideals are dying, if not already dead and buried.

.jpg)